A Lucky Day, Thanks to Grammy

How much was that old glass jar that my husband had inherited from his grandmother

worth? I turned to eBay a commercial site, https://www.ebay.com/

A Lucky Day, Thanks to Grammy

It

might be worth $6 to $65. Mostly what he and I learned from the search is that

it was a Lucky Joe Louis Bank.

Louis was a boxer and his face was used on the bank

after he became heavyweight champion of the world in 1937. Taking that info and

going on an antique class collector site, https://www.kovels.com/collectors-questions/lucky-joe-bank.html I

learned that the jar had once held Nash's prepared mustard and was sold in

grocery stores in Pennsylvania (where Grammy lived) and elsewhere as a

promotion item. This was after the Depression. People needed a reason to buy.

The jar had a dual purpose: it provided food and a place to put your (scarce)

money. Grammy kept the jar on her dresser and gave a coin to grandkids who

might be especially good. This foray into material culture was started because

we had an old piece of stuff on the shelf. What we learned from both commercial

and collector websites was an example of the knowledge gained quickly

On eBay, which says it

facilitates "consumer to consumer and business to business" sales, it's not always clear whether your seller is a

collector, a business, or someone cleaning out the basement. You hope they

abide by the company's stated good-faith policy. There's a place to make

complaints on the site, which means unethical sellers can be barred from using

it.

OTHER SOURCES

Google owns more

than 200 companies

https://www.investopedia.com/investing/companies-owned-by-google/, including

YouTube, a video-sharing website. The search function is crucial there, too.

You go there to learn something (like units in this class or running tips), but

also for random info that can only be classified as entertainment, such as

cartoon and video. Type in "workplace meltdowns" and spend the next

hour saying "ohmigod" and "oh no" and "holy

whatever."

THOUGHTS ON IT ALL

"This exciting prospect of universal, democratic access to

our cultural heritage should always be tempered by a clear-headed analysis of

whether the audience for the historical materials is real rather than

hypothetical," say Cohen and

Rosenzweig. http://chnm.gmu.edu/digitalhistory/digitizing/

Examples of materials I have digitized

Examples of materials I have digitized

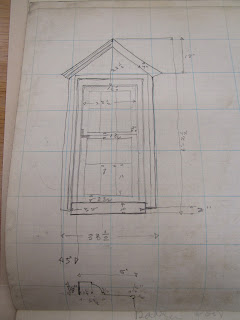

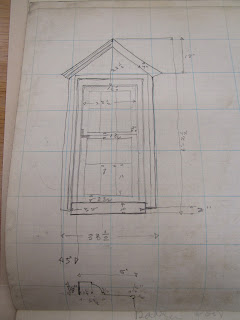

1. At right is a page from an American Historic Buildings Survey (HABS), the 1936 field notes on

an Alexandria house. The original field notes, which are small notebooks filled

with grid paper, are kept in stored collections at the Library of Congress.

http://www.loc.gov/pictures/collection/hh/ A visitor must specifically request

them. These survey reports are not available online or digitized, although some

sketches from select buildings can be found on the library's website. Field

notes are fragile and can only be photographed with approved cameras at select

tables in full view of librarians. The sketch here

shows the measurements of a door fame, pediment and step. From examining this,

an architectural historian may be able to determine its age. The HABS was the

nation's first federal preservation program in 1933. Its purpose was to

document America's architectural heritage.

https://www.nps.gov/hdp/habs/

2. The photo at left is from an Alexandria family collection. It may have been taken in the

late 1880s. The style of dress and hair on the woman must be examined to

determine that, as well as the quality of the photo itself. The family member who

provided this said he believes it is his great, great grandmother as

a young woman in her twenties, or an aunt. He is reluctant to remove the photo

backing (paper) to learn more information at this time. This black-and-white

photo with white frame is about 3 inches wide by 5 inches high. The family

member says he sees resemblance to family members today.

Other sources of digital material: Deeds and will in courthouses are sometimes digitized. Boxes of fragile papers can be digitized so that the information is available to future researchers, but this takes technical skill and money -- the latter, the main obstacle.

FINAL PROJECT

I'm compiling a list of 20 cemeteries from sources in Balch Library, looking for photos on Creative Commons and cemetery websites, and trying to contact people connected with some cemeteries to get permission to use the photos in a story map.

OTHER SOURCES

THOUGHTS ON IT ALL

Examples of materials I have digitized

Examples of materials I have digitized1. At right is a page from an American Historic Buildings Survey (HABS), the 1936 field notes on an Alexandria house. The original field notes, which are small notebooks filled with grid paper, are kept in stored collections at the Library of Congress. http://www.loc.gov/pictures/collection/hh/ A visitor must specifically request them. These survey reports are not available online or digitized, although some sketches from select buildings can be found on the library's website. Field notes are fragile and can only be photographed with approved cameras at select tables in full view of librarians. The sketch here shows the measurements of a door fame, pediment and step. From examining this, an architectural historian may be able to determine its age. The HABS was the nation's first federal preservation program in 1933. Its purpose was to document America's architectural heritage. https://www.nps.gov/hdp/habs/

Other sources of digital material: Deeds and will in courthouses are sometimes digitized. Boxes of fragile papers can be digitized so that the information is available to future researchers, but this takes technical skill and money -- the latter, the main obstacle.

FINAL PROJECT

I'm compiling a list of 20 cemeteries from sources in Balch Library, looking for photos on Creative Commons and cemetery websites, and trying to contact people connected with some cemeteries to get permission to use the photos in a story map.

That's a great example of being able to do a quick search to find more information about a material object. Decades ago, you'd have to go to a library and hope that the library had an antiques catalog that had an image of your jar. It's so much easier now.

ReplyDeleteYou are right that there are always practical considerations, usually money, when it comes to digitizing collections/materials, but from my experience with my postcards, there is also a time constraint--you have to have the time--and you've got to sustain interest in what could be a long project.